Post 65 Awarded 2nd Place in the 2023 Phoenix Veterans Day Parade.

"Although Post 65 delivered a 100 percent first-place float, the parade judges chose to award Post 65 second place, in the 2023 Veterans Day Parade. But no matter, WE truly honored the veterans of the 761 Tank Battalion, aka The Black Panther's history. Their contribution and sacrifices during World War II are indeed remarkable and deserve recognition."

BLACK PANTHERS - 761ST TANK BATTALION

The Black Panthers Enter Combat: The 761st Tank Battalion

The African American 761st Tank Battalion men entered combat at Morville-Les-Vic on November 7, 1944. In an "inferno" of battle, they proved their worth in the first of a series of hard-fought battles.

June 18, 2020

Image: Shoulder sleeve patch of the United States 761st Tank Battalion. Photo by the US Military.

The Black Panther logo for the 761st Tank Battalion. (Credit: Army Heraldry)

The 761st Tank Battalion's motto was "Come Out Fighting." And that it did, from its first engagement at the little Belgian town of Morville-Les-Vic in November 1944 and through heavy combat to the end of the war. But the 761st's fight was not just against the Germans. As a segregated African American unit, it took part in the struggle for racial equality—a battle in which the men of the 761st—the so-called "Black Panthers"—would engage for the rest of their lives.

Brought into existence on April 1, 1942, at Camp Claiborne, Louisiana, the 761st Tank Battalion trained amid the restrictions and racism of the Jim Crow South. First Lieutenant Jack Roosevelt Robinson of the 761st, an athlete who would become one of the greatest baseball players of all time, lost his chance to see combat when he refused to move to the back of a segregated military bus during an incident at Fort Hood, Texas, in July 1944. The 761st battalion's commander, Lt. Col. Paul L. Bates, refused to prosecute Robinson, but his superiors got around that by transferring the lieutenant to another unit, where he was court-martialed. Robinson was later acquitted, but too late to rejoin the Black Panthers.

The 761st arrived in France on October 10, 1944, coming ashore at Omaha Beach and moving into Belgium at the beginning of November. General George S. Patton famously gave the Black Panthers a pep talk, saying in part: "Men, you're the first Negro tankers to ever fight in the American Army. I would never have asked for you if you weren't good. I have nothing but the best in my Army. I don't care what color you are as long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sonsofbitches. Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Most of all, your race is looking forward to your success. Don't let them down, and damn you, don't let me down!" Privately, however, Patton harbored the same doubts that many white officers had about black soldiers and was reluctant to commit them to combat.

On November 7, 1944, the Black Panthers finally got their chance as they attacked the German-held town of Morville-Les-Vic in support of the 26th Infantry Division. Bates, wounded the night before the engagement, was not present, nor were many of his white senior officers. Instead, the first thrust into the town was commanded by African American Capt. John D. Long of B Company, who followed behind the lead Sherman tank commanded by Sgt. Roy King. "I am sure my men thought I was a bastard and hated my guts, but they followed me," later recalled Long, a no-nonsense officer who hailed from Detroit. "They were a well-greased fighting machine."

Right inside the town, King's lead tank was knocked out by a German panzerfaust. Two of King's crew were wounded; their comrades dragged them to safety behind the tank and then went on to kill the soldier with the panzerfaust and the German anti-tank gun crew. King ran to the aid of a white infantryman and was wounded in the process but refused evacuation; he would be killed in action 12 days later. At the end of the battle in Morville-Les-Vic, a German officer would tell Long that that of a Russian tank crew only equaled the conduct of King and his crew "under similar circumstances."

Another tank commander, Staff Sgt. Ruben Rivers encountered a German roadblock that forced his tank to a halt. Under heavy enemy small arms fire, he leaped out of the tank, attached a cable from his Sherman to the roadblock, remounted, and then had his tank pull the obstacle off the road, freeing the tank column to resume the advance and capture the town. Rivers would later receive the Silver Star for his conduct. Like King, however, Rivers would be killed in action several days later; his medal was sent to his family in Oklahoma posthumously.

The Black Panthers captured Morville-Les-Vic on November 7. Three days later, as the advance continued, Sgt. A German anti-tank gun knocked out Warren Crecy's Sherman. Crecy jumped out, took charge of a machine gun on a nearby American half-track, and used it to wipe out the enemy gun crew. On the following day, leading another tank, Crecy again dismounted under fire when his vehicle became stuck in the mud and worked to extricate it. While he was doing so, he saw an enemy machine gun take some of the 26th Division infantry under fire. Without hesitation, Crecy climbed up to his turret machine gun and used it to suppress the enemy. He would repeatedly use the same weapon again that same day—exposing himself to enemy fire and knocking out German machine gun nests and an anti-tank gun. He, too, would receive a Silver Star for gallantry in action.

Capt. Long proudly summed up his pride for the Black Panthers and their conduct. "Not for God and country but for my people and me," he said. "This was my motivation, pure and simple, when I entered the Army. I swore there would never be a headline saying my men and I chickened. In wartime, a soldier is supposed to accept the idea of dying. That's what he's there for; live with it and forget it. I expected to get killed, but whatever happened, I was determined to die an officer and a gentleman. . . . The town of Morville-Les-Vic was supposed to be a snap, but it was an inferno; my men were tigers; they fought like seasoned veterans. We got our lumps, but we took that f***ing town."

In October 1944, the 761st tank battalion became the first African American tank squad to see combat in World War II. And, by the war's end, the Black Panthers had fought their way further east than nearly every other unit from the United States, receiving 391 decorations for heroism. They fought in France and Belgium and were among the first American battalions in Austria to meet the Russian Army. They also broke through Nazi Germany's Siegfried line, allowing General George S. Patton's troops to enter Germany.

During the war, the 761st participated in four major Allied campaigns, including the Battle of the Bulge, the last major German World War II campaign on the Western Front. Germany's defeat in this battle is widely credited with turning the tide of the war toward an Allied victory.

Although the U.S. military would remain heavily segregated until 1948, men of all races around the country volunteered for service when Pearl Harbor was attacked in 1941. Black enlistees were generally diverted to segregated units and divisions, mostly in combat support roles. However, teams of African American soldiers—like World War II's Tuskegee Airmen and the 761st Tank Battalion—played significant roles in military operations.

The 761st commanding officer, Lt. Colonel Paul L. Bates, was well aware of the prevalent racist attitudes towards Black soldiers, so he pushed the battalion to achieve excellence. The 761st Tank Battalion was formed in the spring of 1942 and, according to Army historical records, had 30 Black officers, six white officers, and 676 enlisted men. One of those 36 officers was baseball star Jackie Robinson, who never saw the European theater due to his refusal to give up his seat on a military bus and subsequent court battle.

This majority-Black military unit was known by the nickname "Black Panthers" about the panther patches they wore on their uniforms. Whether the name or the patch—which sported the slogan "Come Out Fighting"—came first is anyone's guess. (Some have speculated they received the moniker because they used German Panzer-Kampf-Wagens, aka Panther tanks. However, records indicate that the 761st used Sherman and Stuart tanks).

In 1944, the 761st was assigned to General George S. Patton's Third Army in France. Patton was well known for his colorful personality and, upon meeting the troops, exclaimed:

"Men, you're the first Negro tankers to ever fight in the American Army. I would never have asked for you if you weren't good. I have nothing but the best in my Army. I don't care what color you are as long as you go up there and kill those Kraut sons of bitches. Everyone has their eyes on you and is expecting great things from you. Don't let them down, and damn you, don't let me down!"

By all accounts, they didn't. Starting on November 7, 1944, the 761st Battalion served for over 183 consecutive days under General Patton. By comparison, most identical units at the front line only did one or two weeks. During the Battle of the Bulge, the 761st was up against the troops of the 13th SS Panzer Division. Still, by January 1945, the German forces had retreated and abandoned the road, which had been a supply corridor for the Nazi army. By the end of the Battle of The Bulge, three officers and 31 enlisted men of the 761st had been killed in action.

In May 1945, the Black Panthers were part of the Allied forces who liberated Gunskirchen, a subcamp of the Mauthausen concentration camp. One woman released by the unit, 17-year-old Sonia Schreiber Weitz, described the soldier who saved her in the poem "The Black Messiah":

A Black GI stood by the door

(I never saw a Black before)

He'll set me free before I die,

I thought he must be the Messiah

After the war, the Army awarded the unit with four campaign ribbons. In addition, the men of the 761st received a total of 11 Silver Stars, 69 Bronze Stars, and about 300 Purple Hearts. Back at home, though, the surviving members of the 761st returned from Europe to a still-segregated nation. Texas native Staff Sgt. Floyd Dade Jr. described the contradictions for Black soldiers returning to the United States in an oral history, saying, "we didn't have equal rights…democracy was against us. I was fighting for my country."

READ MORE: Black Americans Who Served in WWII Faced Segregation Abroad and at Home

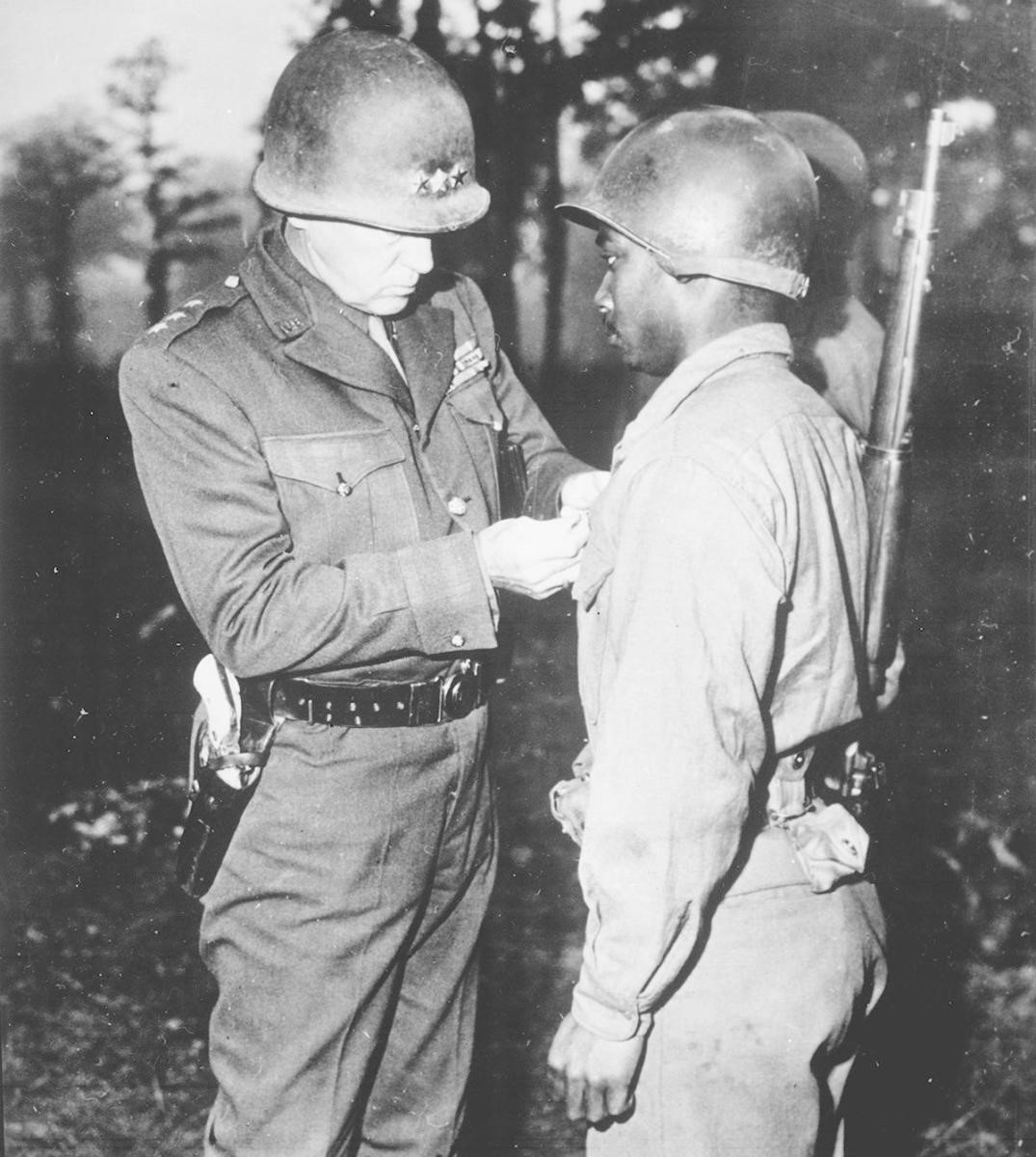

General George S. Patton, U.S. Third Army commander, pinning the Silver Star on Private Ernest A. Jenkins of New York City for his conspicuous gallantry in the liberation of Chateaudun, France, 1944.

The National Archives

When Staff Sgt. Johnnie Stevens attempted to catch a bus home to New Jersey from Georgia's Fort Benning, but the bus driver refused to let him board. Jackie Robinson, whose charges for refusing to give up his seat on the military bus were eventually dropped, later noted that men of the 761st had died fighting for a country where they didn't have equal rights.

As the years passed, the achievements of the Black Panthers began to receive more recognition. In 1978, the 761st received a Presidential Unit Citation, which recognizes units that "display such gallantry, determination, and esprit de corps in accomplishing [their] mission under extremely difficult and hazardous conditions as to set [them] apart from and above other units in the same campaign."

In 1997, President Bill Clinton posthumously presented the Medal of Honor to seven men who had served in the battalion. "No African American who deserved the Medal of Honor for his service in World War II received it," Clinton noted.

"Today, we fill the gap in that picture and give a group of heroes, who also love peace but adapted themselves to war, the tribute that has always been their due," Clinton continued. "Now and forever, the truth will be known about these African Americans who gave so much that the rest of us might be free."